The case for Nushell

August 30, 2023 -Recently, I had a chat with some of my friends about Nushell and why they stuck with traditional shells like bash/zsh or the "new" hotness like fish rather than using Nushell. After chatting with them, my brain kept bubbling away at the state of how folks were using their terminals and the end result is this blog post.

In this post, I make the case for really taking a hard look at Nushell and also for generally asking the question: "can the state of shells be improved enough to overcome the inertia of sticking to what you know?"

The lay of the land

Let's take a look at some of the offerings out there that people are using everyday.

Bash/zsh

Bash, originally a set of improvements on the Bourne shell, has grown to be the default shell for almost all Linux distros. That's generally people's first experience when they hit the terminal. It's what they see when they log into a remote machine. It's reached the definition of ubiquitous.

I also throw 'zsh' in here as well. Apple's macOS switched from bash to zsh, an operationally similar shell but created a bit more recently.

Bash at this point has become so well known that people often confuse support for bash-isms as part of the POSIX standard, but we'll talk about that later.

Pros: it's everywhere. Learn once, run anywhere.

Cons: as a language, bash/zsh feels a bit too retro. It doesn't offer any of the modern programming language style, tool support, etc folks would be used to from other languages. In truth, bash was never really meant for writing the kind of large scripts that people are maintaining today.

Example for loop in bash:

#!/bin/bash

for i in `seq 1 10`;

do

echo $i

done

Fish

As fish's website says: "Finally, a command line shell for the 90s"

It's enough to elicit a smirk, because you know it's a bit true. The bash/zsh style shells are getting left behind by something that feels a bit nicer, has nicer completions, looks nicer (you can get similar improvements out of bash if you work at it, but fish ships with them out of the box)

Fish also bravely steps away from the shell scripting form of bash to something a bit more readable.

Example for loop in fish:

for i in (seq 1 10);

echo $i;

end

Pros: the interactive experience of fish does feel quite a bit nicer that bash/zsh out of the box. Scripting is a bit nicer.

Cons: As it says on the tin, it's a shell for the 90s. It ain't the 90s anymore.

PowerShell

Coming into 1.0 at 2006, PowerShell is one of the first shells to really draw a line in the sand to say "enough, we're going to do things differently". The unix style of pipelines, where commands communicate via text to each other was replaced by a .NET engine that passed objects between commands.

The impact wasn't immediately obvious but as devops folks (and others) discovered what was possible when you have ways to work with data directly a fanbase grew.

Example of a for(each) loop in PowerShell:

foreach ($i in 1..10) {

echo $i

}

PowerShell came with an opinionated design that focused on verb-noun naming, improvements to shell syntax, and a vast set of functionality drawn from the .NET ecosystem.

Pros: it's a structured shell - you can actually work with objects rather than text. Powerful set of tools and capabilities taken from .NET.

Cons: I'll go ahead and say it: PowerShell was never really designed to be a language first. The verb-noun convention forces a style that feels very awkward coming from other languages. Worth a mention: earlier versions of PowerShell were Windows-only and modern crossplatform support lacks some of the features of the earlier versions.

Other shells

When I was coming up, there were a lot of other shells, including the csh/tcsh family. Having said that, I don't know anyone who is using any of the other family of shells. Bash/zsh and to some extent fish really dominate the developer mindshare.

Hold up, we really need to talk about POSIX

We really need to take a minute and talk about POSIX before we continue. A lot of folks have leveled "but it's not POSIX" as an argument against using Nushell, but I'd like to turn that around and ask the question:

"What's so good about POSIX?"

Most folks when asked would likely point to it as a common ground that code can be ported to. In reply, I'd like to quote a few bits of the POSIX standard.

The following are reserved words in the POSIX standard for shell scripting:

- case

- do

- done

- elif

- else

- esac

- fi

- for

- if

- in

- then

- until

- while

Yes, really. fi and esac are a joke that never found their end. No one would design a language that did that with a straight face these days.

Let's take a quick look at the number of flags common Unix commands ship with. These are on my macOS system, so ymmv.

| command | number of flags |

|---|---|

| ls | 45 |

| man | 15 |

| ps | 29 |

If you look through the flags of ls to see why it has so many, notice how many are configuring what ls is displaying. In a real sense, this is going against the underlying philosophy of unix pipelines. Rather than composing a pipeline to get the display you want, you're learning a language of flags for each command to configure the display.

Let's talk about exit codes. Actually, wait, I already did that. As I point out in the post, the standard says:

"The value of status may be 0, EXIT_SUCCESS, EXIT_FAILURE, [CX] [Option Start] or any other value, though only the least significant 8 bits (that is, status & 0377) shall be available from wait() and waitpid(); the full value shall be available from waitid() and in the siginfo_t passed to a signal handler for SIGCHLD. [Option End]"

Sure - we all still use 8-bit machines while flipping through a manual we printed trying to find the exit code description to understand why a command failed.

I hear you: "but, look, it doesn't matter how archaic this stuff is, if we all agree to use it things keep working."

I dunno - these arguments just don't hold up. We'd still be using C as our main systems language because it's the most documented, most portable, etc. But, by and large, we don't. We're increasingly choosing other languages.

The truth is, in 2023 if someone asked us to design a system, we wouldn't design POSIX. If, in 2023, someone asked us to design a shell language, we wouldn't design bash/zsh. This matters.

Show us the money

I make some pretty bold statements in the above. There is a heritage of technology that got us to this point. While that heritage is important, it's not without its drawbacks. Are there better ways of doing it?

Why structure matters

Before we get into talking about Nushell, let's talk about why structured data matters.

In the Unix pipeline way of thinking, text passes between commands. This is very flexible, but has a major problem: both the outputting command and the inputting command have to agree what shape that text will take so the info can be passed. This locks representation to presentation, disallowing commands from evolving their output over time. As we showed earlier, it also encourages a proliferation of flags.

That's annoying. Does separating the structure from its presentation help us?

> ls | where size > 10kb

I always start with this example when showing off Nushell, because not only is it immediately readable, we didn't have to dig through any flags to figure out what we needed to pass to ls to get that. We also aren't parsing anything from ls. Instead, the data is passed directly to where, which handles it directly.

Commands already know this structure, why not make use of it?

The same where command works on other things. For example, we can process the output of the ps command:

> ps | where cpu > 40

Or open a csv file and processing its rows:

> open fields.csv | where area > 5

And so on. It's the same where regardless of where the data is coming from. It also gives us the freedom to present the data however we want.

Why Nushell matters

Nushell is designed to be a language

I had the good fortune of being a part of some prominent programming language teams, including helping to create TypeScript and helping create Rust's error messages as part of the Rust team in Mozilla. Designing languages to be easy to use, easy to read, easy to scale up, and easy to debug is something I care about and have worked on for many years.

To that end, Nushell is designed with an eye towards being readable at a glance.

Let's do a for loop in Nushell:

for i in 1..10 {

print $i

}

(aside: "but why do variables have dollar signs?". Turns out the flexibility of shell programming allows paths to not use quotes, so it's nice to tell a difference between cd foo and cd $foo)

This eye towards usable design shows up in many ways. Working with data is improved by not only having structure, but also being able to pattern match against it. Here's an example of pattern matching a list in Nushell:

match $list {

[$one] => { print "one element list" }

[$one, $two] => { print "two element list" }

[$head, ..$tail] => { print $"the tail of the list is ($tail)" }

}

In a way, working in Nushell should feel at home both interactively as a shell and as a full scripting language. We've had folks write COVID reporting software in Nushell, research experiments, even entire shells for well-known database services.

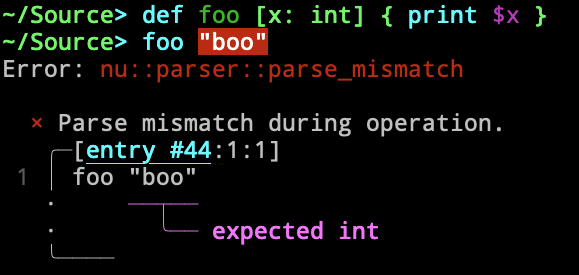

Nushell is typechecked

Since Nushell doesn't treat all data as text, you can represent tables, records, numbers, booleans, etc directly in the language.

As a result of this, Nushell is fully typechecked. Common errors can be caught early and shown to you before the script even runs.

Taking what we learned from TypeScript - the types also feed into another important tool.

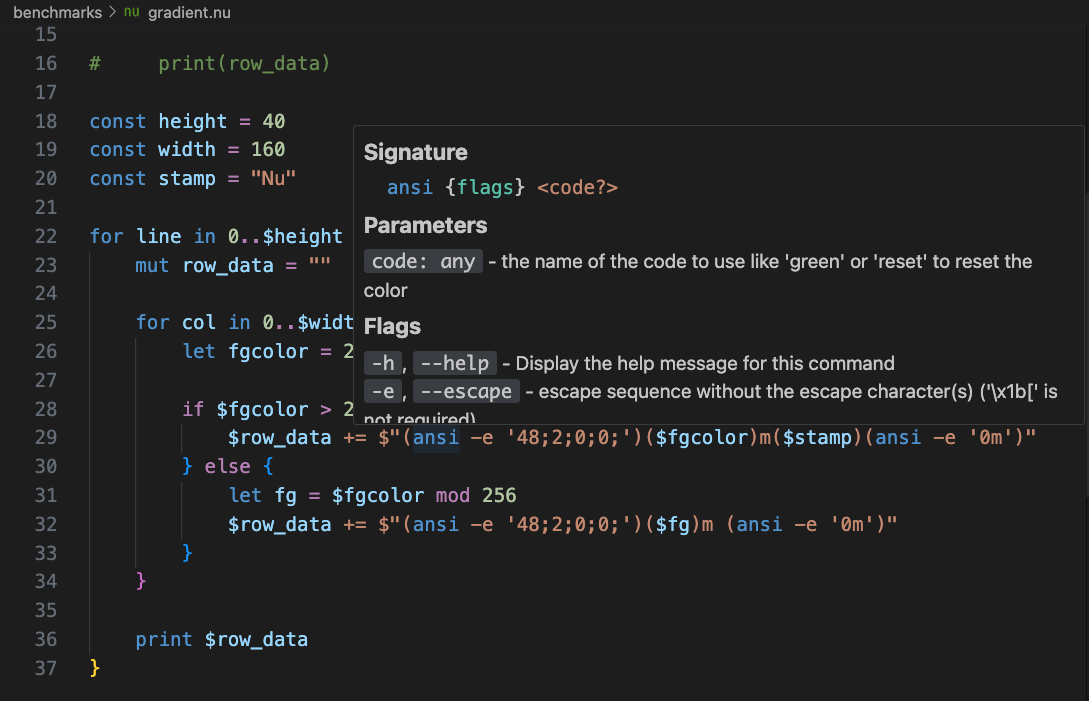

Nushell has IDE support

The types, autocompletion, and early error reporting feed into an engine in Nushell that knows a lot more about your code. As a result, you can write scripts and then work with them using the IDE support Nushell provides. Seeing errors, jumping to definitions, getting documentation on hovers, etc are all part of the Nushell experience.

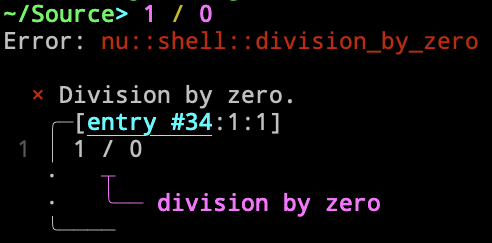

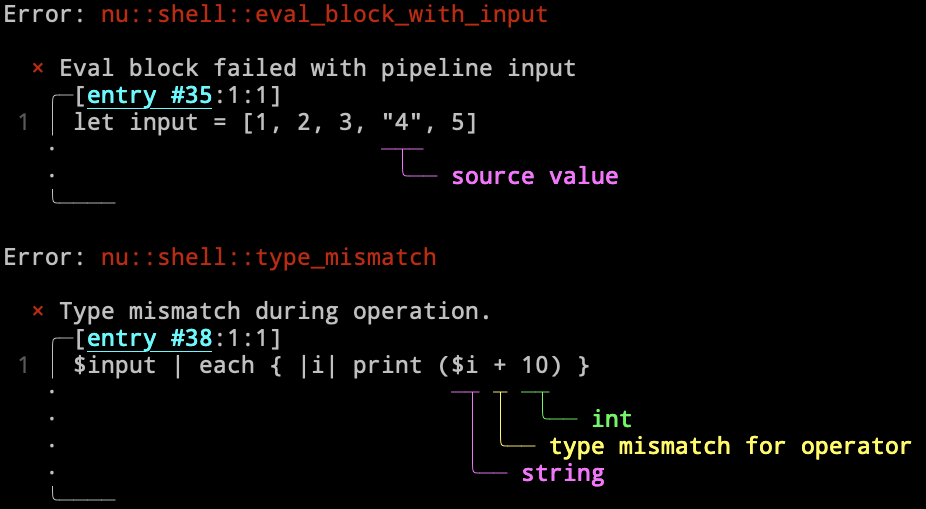

Nushell has nice errors

In Nushell, we make extensive use of remembering where data comes from, as well as what caused an error. Simple errors, like division by zero, are shown clearly:

A more complex error may need to show more to help track down where a mistake came from. Let's say you've accidentally put a string in your list of numbers, and then tried to process it:

Nushell has a SQL-like style

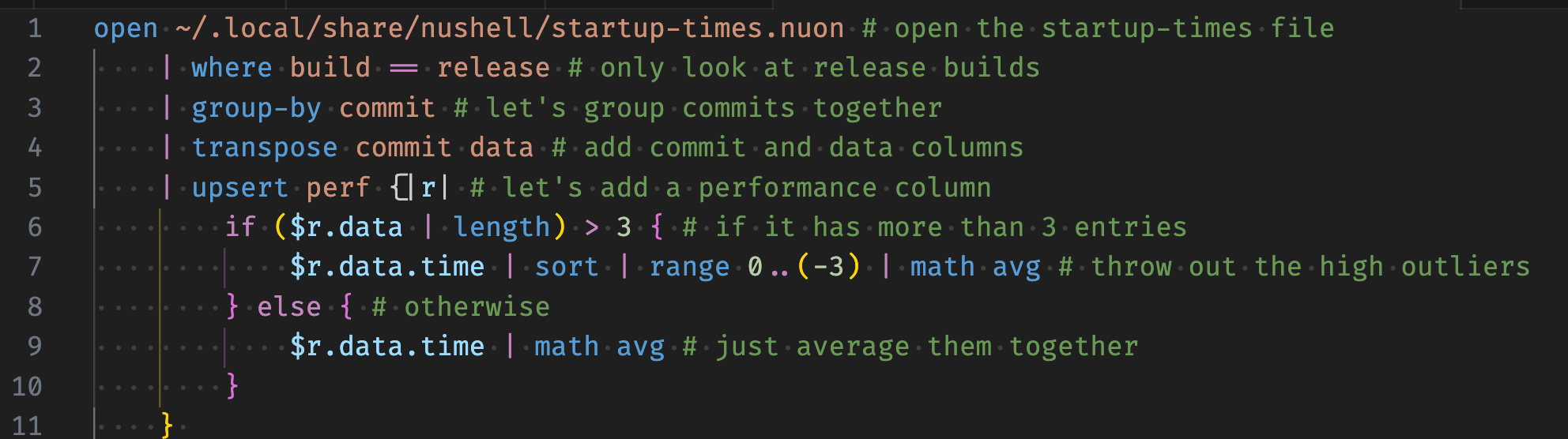

When you start using Nushell to compose pipelines, you'll notice that it has a distinct SQL-like style. Data flows through each stage, and you build up what you want to do to it as you add more commands.

This gives Nushell a distinctive design that encourages experimentation and exploration.

Nushell is, and has always been, crossplatform

An important decision we made from day 1 was to be crossplatform. You can run Nushell on Windows, Linux, and macOS (and BSD, and Android) and get the same experience. You can easily write scripts in a way that they can be run across different platforms. Everything that you learn transfers between OSes without friction.

Is Nushell good enough to overcome the inertia?

I distinctly remember going to a SIAM conference many years back and giving a talk on the Chapel programming language. Even back then, it was a clever language. In a couple lines, you could write code that could distribute and process a matrix across a network of computers. Coming from a lineage of array languages, it ate up data parallel processing. The equivalent code in other languages looked verbose in comparison.

I went through my talk, hoping I'd done a decent job of conveying the main points, and at the end, someone in the audience stood up and said "but I can do all this in C++".

He proceeded to explain that if he could recreate many of the techniques we showed all as part of a C++ library that people could use. At this time, I wasn't sure how to respond other than "but you don't have to, we already built this language" but he couldn't be swayed. If it wasn't C++, he didn't want it.

Fast forward a couple years, and I'm standing in front of a JavaScript audience giving a similar talk, this time promoting TypeScript. I remember the kind of politely confused looks on people's faces as I showed off the features TypeScript offered. There was a similar sense of "why do we need to leave JavaScript?".

To answer whether Nushell can overcome this kind of inertia, I'll pose two questions:

- Is Nushell compelling enough for a single person to adopt it?

- Would adopting Nushell broadly as a community move the needle?

Let's tackle the first question. Time and again, as people try Nushell, they come back with quotes like "this is the most excited I've been about tech in 15 years". It has a fanbase that loves it, and that fanbase is growing. It reminds me of the early days of Rust, just after hitting 1.0.

To the second question: would adopting Nushell broadly actually improve things noticeably? Without a doubt. I say this without any reservation. Thinking of our shells as structured, interactive processing engines opens up the doors to a much wider array of things you can do with them. The commands would be far simpler than their POSIX equivalents and would compose far better. They'd benefit from the full knowledge of the data being shared between them. Adaptors could be made to connect to all parts of the system, allowing you full, structured interaction with everything you have access to.

In essence, as the saying goes, we'd be building a skyscraper starting from the 15th floor instead of the 1st.

It's time to be honest about what Nushell is

It's time I come clean about what Nushell is. Nushell isn't exactly a shell, at least not in the traditional Unix sense of the word. Nushell is trying to answer the question: "what if we asked more of our shells?"

Nushell is really an interactive, data-focused scripting language with shell capabilities. It merges these three things into one:

- A fully-typed scripting language

- An interactive shell

- A data processing system (that can also handle large data loads via dataframes)

Rather than these being three separate ideas glued together, in practice it feels like Nushell is treating everything you interact with as data. This allows you to pull together different kinds of data, and know that the same commands will work over them.

You might look at that list and think you don't need all that, but the way I might frame it is this: it's nice to have it when you need it.

I don't need to do heavy data processing everyday, but it's nice to not have to shift what I'm doing at all when I need to do it. I don't have to download new utilities or switch languages. It's all right there. Need to write a script to load some files and handle some directory processing? Still right there. Need to throw together some web query that outputs the top download results for a github repo? You guessed it, all still right there.

This is just scratching the surface, really. Nushell has a plugin system that allows more capabilities to be added based on your needs. We already have plugins that add a variety of additional file formats, querying capabilities, and more.

It's okay to have nice things

Nushell was built with a simple idea: working in the shell, writing code, and processing data should be fun. To that end, we work hard to make Nushell feel nice.

You can write readable scripts that come with their own documentation, and then come back to them 6 months later and still understand what they're doing.

You can sit in the shell and play with pipeline ideas until one grows into a scripting project and then effortlessly transition your experiment into a full script.

That's it

That's my case. It's okay to have fun. It's okay to write attractive, well-documented code. It's okay to leave the designs of the past behind when they no longer fit the present day.

It's okay to move on to better ways of doing things.